Tips and tricks for successful classification

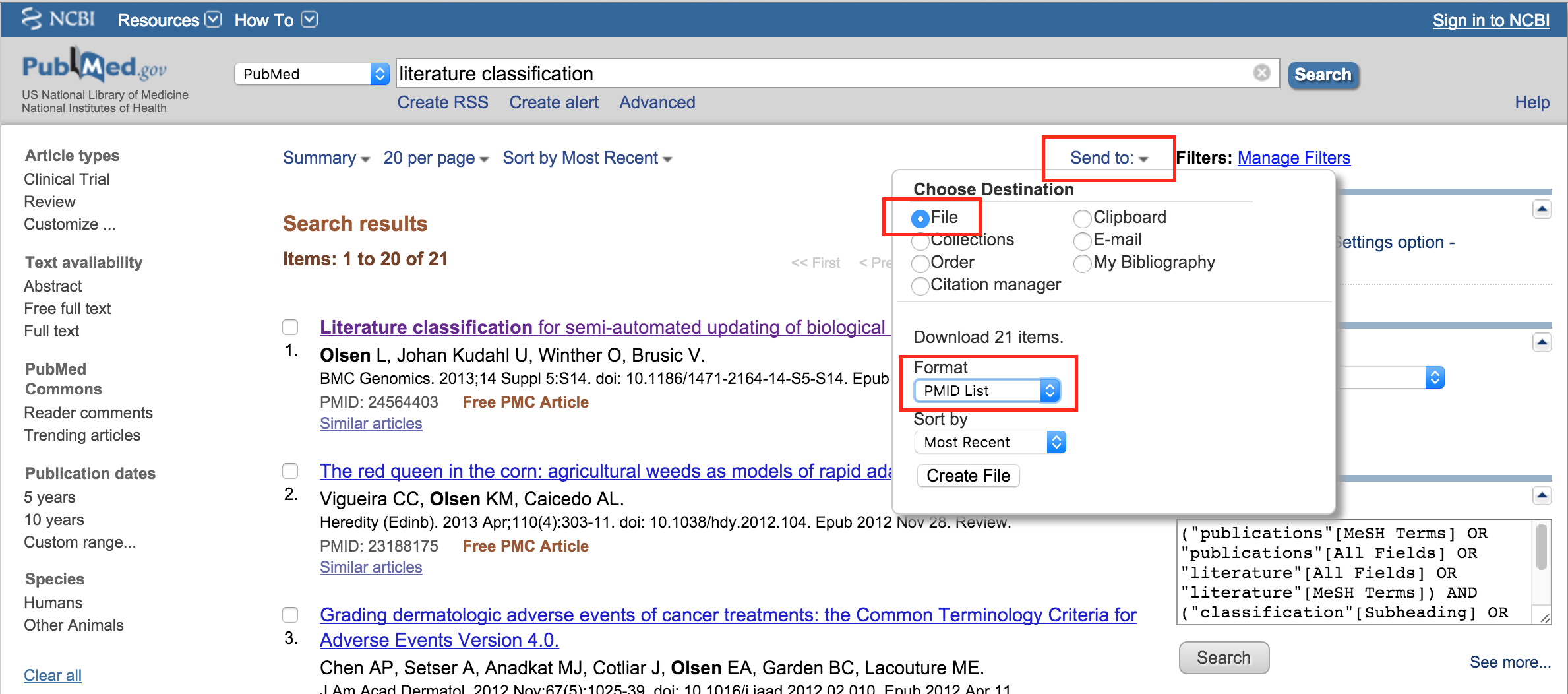

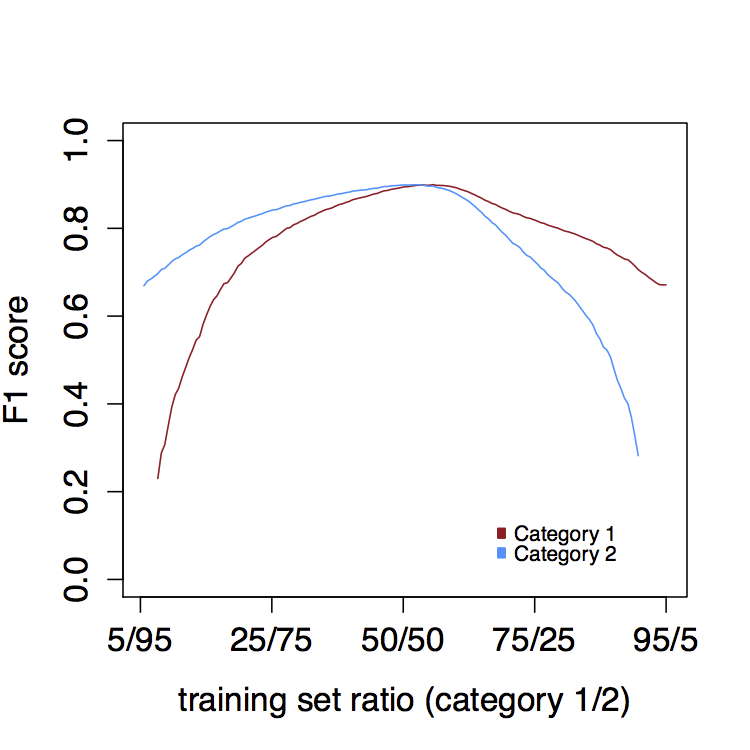

The performance of BioReader depends heavily on the size of the training set, how well the training set captures the differences between classes, and the inherent ability of a given set to be separated into classes. We recommend at least 20 manually curated abstracts in each category, and ideally more than 100. We conducted a test on two relatively homologous groups of abstracts – all within the field of immunology, but some containing epitope information, and others not. Iteratively training a classifier and slowly increasing the training set size, we found that a lot is gained when increasing from 50-250 abstracts, but beyond that, performance gain is minimal (Figure 2).

BioReader can help you distinguish between relevant and irrelevant literature - even in cases where it is not obvious upon first glance. In fact, the more similar your negative articles are to your positive, the better the results - “subtle differences” is our speciality, and you probably don’t really need BioReader's help to tell the difference between psychology papers and plant science papers.

Figure 2: Learning curve for five-fold cross-validation with glmnet on corpora ranging from 50 to 1500 abstracts in intervals of 10 abstracts (average over 100 iterations).

Figure 2: Learning curve for five-fold cross-validation with glmnet on corpora ranging from 50 to 1500 abstracts in intervals of 10 abstracts (average over 100 iterations).

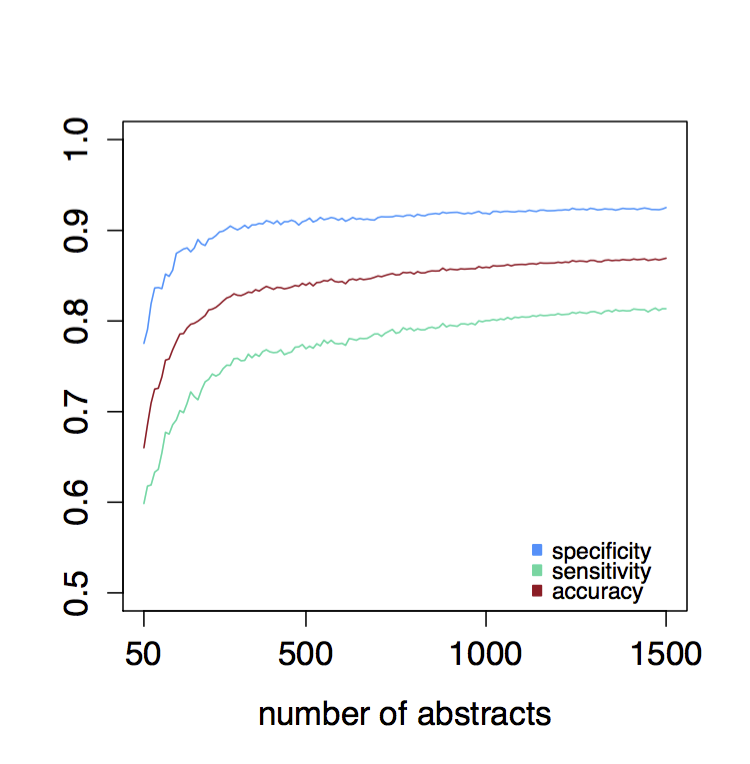

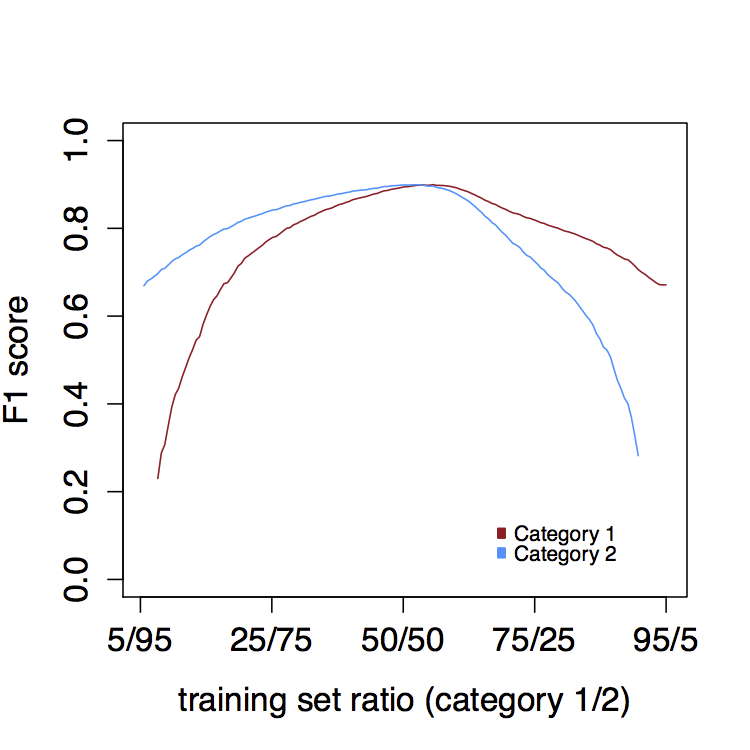

Similarly, it is essential that you keep the training set balanced (an equal number of abstracts in each training category). Ideally, a training sets will be in a 50/50 ratio between the two categories, since an over representation of either category will skew the classification. Adding more abstracts in one category will increase the recall of that category at the expense of the precision (Figure 3).

Figure 3: F1 scores for category 1 and category 2 classification at varying proportions of training set size (total 750 abstracts) for each category in intervals of 10 abstracts (average over 100 iterations).

Figure 3: F1 scores for category 1 and category 2 classification at varying proportions of training set size (total 750 abstracts) for each category in intervals of 10 abstracts (average over 100 iterations).

Lastly, it is important that you only attempt to separate into two categories in each run. It is possible to further categorize resulting categories in an iterative manner, e.g. first classify on diseases categories, followed by an additional classification on, say, the host organism.